WPF in the Enterprise

October 31, 2007

Most software developers don’t create off the shelf software packages, I’d hazard a guess that very few do. The reality is that most developers work on Line of Business applications, these are applications that have a user base measured in the hundreds, or the low thousands if your lucky. These are the applications where WPF needs to gain some traction.

These LOB applications are built to solve a business need and the sad fact about them is that the vast majority of them are ugly. There aren’t many Miss Worlds in the LOB realm.

If you take your average WinForms LOB application you’ll find a UI that is put together with minimal thought to the aesthetics. They’ll be a whole host of usability crimes and the visual style will be based around whatever the custom control package they’re using provides. The thing as a whole will have a lack of visual cohesion, which will be a function of the number of developers who worked on it. Its sad but true that most developers are rubbish at designing good UI’s.

Creating the UI for an average LOB application is fairly straightforward with Windows Forms. Everything we need is usually there. The tools, the framework and the environment are suited to the job at hand. Now this is the world where WPF has to live and thrive.

Here are some of my observations.

WPF is harder than WinForms.

There learning curve is steeper. Routed Events, dependency properties etc are not straight forward. Its not easy to pick up WPF quickly, and there isn’t much of your WinForms knowledge that has a high relevance in the world of WPF. Starting a new project with a team that hasn’t developed with WPF is going to require a reasonable amount of time to let them get up to speed with the technology.

Tool support is lacking.

The WinForms designer is very good. It’s intuitive to use and most people can just work it out without any intervention. The WPF designer in Visual Studio 2008 just isn’t up to the same standard. Lets look at the property windows for a button in the WinForms designer and the VS WPF Designer:

| Windows Forms: | WPF: |

To me Windows Forms is more intuitive, where are the events in VS WPF Designer, what the hell am I supposed to type in the BitmapEffectInput or Opacity mask properties? Where is the ‘…’ button that gives a dialog for setting these.

Its not all doom and gloom for WPF. Expression Blend is great, it works really well and is very stable. I know that Blend is pitched at designers but I think its great for developers too. Why did they create two designers; why doesn’t Visual Studio host a variant of the blend engine. They’ve done it for the Web designer in VS2008, that’s based on the core engine from Expression Web.

We don’t have designers

One of the big points that Microsoft wanted to get across when evangelizing WPF was the designer developer seperation and how WPF let them both easily co-exist within a project. For most LOB applications the developer is the designer. The problem is that they often have zero design ability. Eric Sink had a great post about WPF’s dirty secret, there is no golden ticket to a beautiful UI. Its just as easy to create an ugly app in WPF as it is with WinForms. There is no substitute for a bit of real graphical talent.

At times WPF makes it to easy to commit crimes against usability. Take Animation, its relatively straightforward to implement. But just because you can doesn’t mean that you should.

Here’s an idea, how about some pre-rolled styles with Visual Studio. The kind of thing that can be used to jazz up an otherwise dull application.

They rejected the animated 3D feature, they just want a grid instead.

Lets be honest, 3D is great and I love the fact that its so simple in WPF (well at least compared to the other ways of doing 3D). We want to create something that lets us play with these new features and dangle our feet in the world of quaternions but what we normally end up having to implement is a grid. Now the WPF grid is… yes, we all know there isn’t one.

Now I’m not trying to knock WPF. I think its a great technology. Its full of some amazing features and technologies: 3D, improved data binding, scalable UI’s, hardware rendering, proper text rendering, animation, documents and so on. It just isn’t going to automatically replace Windows Forms, there is still work that needs to be done to make it the default choice for every new project that involves some kind of desktop app. Its good to see announcements like the WPF Composite Client, these are the sort of things that we need to drive the adoption forward.

Hosting MSBuild

October 29, 2007

Most people tend to use MSBuild via a few standard scenarios. Inside Visual Studio, from the command line and invoked by a continuous integration system such as Cruise Control are probably the most common.

The MSBuild framework is very flexible and we can very easily host the build engine ourselves with very little effort.

All we need to do is:

Add a reference to the MsBuild engine and framework.

Its often a good idea to run MSBuild in its own thread. If your application is running in an MTA thread then you’ll need to do this otherwise you will get a lot of warnings. If you want to see this try creating a Powershell script that invokes MSBuild through .net rather than calling msbuild.exe.

Create and invoke the engine:

Engine engine = new Engine(); engine.BinPath = @"C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v2.0.50727\"; ConsoleLogger logger = new ConsoleLogger(); engine.RegisterLogger(logger); bool result = engine.BuildProjectFile( @"C:\Projects\MyProj.csproj", "Build"); if (result) { MessageBox.Show("Build Suceeded"); } else { MessageBox.Show("Build Failed"); }

There are two loggers that come with the base framework, the ConsoleLogger and FileLogger. Its pretty obvious from there names as to what they do. If we are hosting msbuild then chances are they won’t meet all of there needs. Fortunately we can roll our own fairly easily by implementing the ILogger interface.

public class MyLogger : ILogger

Then set up some events to handle all of the logging.

public void Initialize(IEventSource eventSource) { eventSource.ProjectStarted += new ProjectStartedEventHandler(eventSource_ProjectStarted); eventSource.TaskStarted += new TaskStartedEventHandler(eventSource_TaskStarted); eventSource.MessageRaised += new BuildMessageEventHandler(eventSource_MessageRaised); eventSource.WarningRaised += new BuildWarningEventHandler(eventSource_WarningRaised); eventSource.ErrorRaised += new BuildErrorEventHandler(eventSource_ErrorRaised); eventSource.ProjectFinished += new ProjectFinishedEventHandler(eventSource_ProjectFinished); }

Write some handlers for these events. This is where we get the details of the error/warning/message and handle it as we please. It this example we are just writing it to the debug output window.

void eventSource_WarningRaised(object sender, BuildWarningEventArgs e) { //Handle the logging event System.Diagnostics.Debug.WriteLine(e.Message); }

Worker threads and the Dispatcher in WPF

October 29, 2007

WPF is very similar to Windows Forms in terms of its multi threaded capabilities. While it does use multiple threads as part of the rendering pipeline as far as a user of WPF is concerned the UI is single threaded. So the old rule that we must do all of our UI updates from the main thread still applies.

In Windows Forms we would use Control.Invoke to send work back to our main thread. WPF is very similar. It provides the Dispatcher which allows us to Invoke back onto the main thread.

Its reasonably straight forward to use. We provide a delegate that we would like to run on the main thread, and ask the Dispatcher to run it using either Invoke (for synchronous running) or BeginInvoke (for async running).

Consider the following example. We have a simple window with a label and on startup we create a thread that simulates a long running task (in this case calculating Pi, with a few sleeps to slow it down). The thread will then use the Dispatcher to periodically update the UI with its progress.

Xaml:

<Window x:Class="DispatcherApp.Window1" xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation" xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml" Title="Window1" Height="111" Width="535"> <Grid> <Label Margin="13,22,19,24" Name="label1">Label</Label> </Grid> </Window>

C#:

using System; using System.Windows; using System.Threading; namespace DispatcherApp { delegate void UpdateTheUI(string newText); public partial class Window1 : Window { public Window1() { InitializeComponent(); Thread thrd = new Thread(new ThreadStart(this.CalculatePi)); thrd.Start(); } void CalculatePi() { double res = 0.0; for (int i = 0; i < 20; i++) { Thread.Sleep(1000); res += Factorial(2 * i) / (Math.Pow(Factorial(i), 2) * ((2 * i) + 1) * Math.Pow(16, i)); string piText = (res * 3.0).ToString(); this.Dispatcher.BeginInvoke( System.Windows.Threading.DispatcherPriority.Normal, (UpdateTheUI)delegate(string text) { label1.Content = text; }, piText); } } double Factorial(long value) { long returnVal = 1; for (long i = 2; i <= value; i++) { returnVal *= i; } return (double)returnVal; } } }

Its worth noting that there are other ways to do this in WPF. The BackgroundWorker provides similar capabilities and might be more appropriate in some circumstances.

ReaderWriterLock Reborn

October 19, 2007

It turns out the ReaderWriterLock has a few flaws, it’s not that it doesn’t work. It just doesn’t work as well as it should. Microsoft have admitted its not as good as it could be and have provided another Reader-Writer lock implementation in .net 3.5 called ReaderWriterLockSlim.

They have decided not to change the existing ReaderWriterLock for backwards compatibility issues, instead we have two versions. For virtually all use cases we should be switching to the new ReaderWriterLockSlim but there are a few subtle differences which can affect which one we choose.

ReaderWriterLock

- Is slow, about 6-7x slower than a Monitor.Enter

- Favors read locks, if you have lots of read lock requests then it can prove difficult for a write to get a lock. Depending on how many of which type of lock gets requested you can end up with a situation where your Write requests are waiting a long time.

- Upgrading a reader to a writer is not atomic.

Jeff Richter has a great MSDN article about its deficiencies.

ReaderWriterLockSlim

- Is much quicker, only 2x slower than a Monitor.Enter.

- Favors writes over reads.

- Upgrades from reader to writer are atomic.

And the cons, which will determine if we should be using the original.

- Doesn’t handle ThreadAbort exceptions or Out Of Memory Exceptions very well. Can end up pegging the CPU at 100%. This should not really be much of an issue in practice since we shouldn’t really be forcing aborts that raise thread abort exceptions and out of memory exceptions are extremely difficult to recover from anyway.

- Not suitable for use in hosted CLR scenarios such as SQL Server, use the original if you want to run your code inside of SQL server.

Synchronization with the ManualResetEvent

October 15, 2007

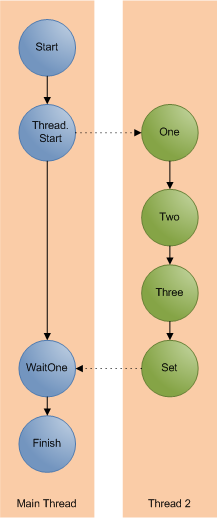

The lock statement is probably the best known and most used of the synchronization methods in C#, but there are many more. Of these the Manual Reset Event is worthy of a mention. It allows very simple cross thread signalling. This allows us to create threads that wait for things to happen on other threads before proceeding.

The principle of the ManualResetEvent is fairly simple. One thread waits for the other thread to signal. Once it has signalled the first thread carries on. The waiting is done with .Wait and the signalling with .Set. We can ready the whole thing for use again (reseting it) by calling .Reset.

The little program below shows a very simple example of this. The main thread creates a second thread. The main thread now waits. The second thread counts to three, when its done this it signals. The main thread picks up the signal and carries on.

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading;

namespace ManualResetEventTest

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Console.WriteLine("Main Thread Started");

ManualResetEvent sync = new ManualResetEvent(false);

Thread thread = new Thread(new ParameterizedThreadStart(Thread2));

thread.Start((object)sync);

sync.WaitOne();

Console.WriteLine("Main Thread Finished");

}

static void Thread2(object parameter)

{

ManualResetEvent sync = (ManualResetEvent)parameter;

Thread.Sleep(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(1));

Console.WriteLine("One");

Thread.Sleep(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(1));

Console.WriteLine("Two");

Thread.Sleep(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(1));

Console.WriteLine("Three");

sync.Set();

}

}

}

When we run the program we get the following output:

Main Thread Started

One

Two

Three

Main Thread Finished

This is how the flow of execution looks

There is of course the AutoResetEvent which is nearly identical except it automatically resets after it has been signalled, so it’s immediately ready to use again.

C# and its Learning Curve

October 12, 2007

Back in its day Visual Basic had a reputation as being overly simple. In the dot com boom of the late 90’s people who had never been software developers or who had no natural interest in software development jumped on a bandwagon in search of a quick buck. The reason they could do this was because the common language of the day allowed them to, VB was simple enough that they could wing there way through a simple software project. The void between VB and C++ was huge, you had to be good to develop in C++. VB didn’t demand such high standards. With the demand for developers so high these people with no previous experience in development could fake there way through a few jobs armed with a handful of ‘… for Dummies’ and ‘Teach yourself … in 21 Days’ books.

Fast forward a few years to the present day. Visual Basic as it was has pretty much disappeared, on the Microsoft side C# has rightfully taken its place. Most of our bandwagon developers have probable all changed careers and become plumbers. C# and .Net are more complicated than VB. They have the features and complexities of a proper language; Threads, delegates, proper object orientation and much more. Our bandwagon developer of yester-year never had any of this complexity and this is one of the reasons they could get away with what they did. VB had a shallow learning curve and the barrier to entry wasn’t so high.

Since hitting the scene in 2002 C# and .net have grown in power and complexity. Generics, LINQ, anonymous methods, WPF and much more have all appeared since that first release. Learning C# to the level that one would expect from a good developer is a lot harder than what it was in 2002. There’s more to it and some of the concepts are more taxing to get your head around.

Take WPF and WinForms. WPF is a great technology and I think there should be a real push to get desktop applications to use it but its harder to learn than WinForms. Attached properties, routed events and all the other new concepts are not intuitive or obvious to a lot of people. The learning curve is steeper than it is for WinForms and not every one will be able to make it all the way to the top.

What does this mean in reality? Software development isn’t easy, its not a meal ticket for those that want to make some easy money. To be sucessfull you need to be good. For someone to be proficient developer in .net 3.5 they are going to have to learn a lot more than they would have to get to the same level in .net 1. The increased size and steepness of the learning curve is going to raise the barrier to entry. It may not be that there are is going to be a shortage of people coming forward with C# skills, it may be that those with the top skills and the deepest understanding are going to be even harder to find than they are today.

Vista booting and running from a USB Disk

October 10, 2007

I think i’ll have to create one of these myself, it seems quite straightforward.

Heisenbugs and Schroedinbugs

October 9, 2007

While batteling with some random bugs on a Friday afternoon I remembered these particular classes of bugs. I think its the names that appeal to the inner geek in me. Clever names but very geeky.

If you can’t remember the details of these or you’ve never heard of them before here’s a quick recap.

Schroedinbugs

Named after the famous Schroedingers Cat thought experiment. A Schroedinbug is one that only appears when you read the code and find something that should not work. At this point it stops working even though it was previosuly working fine.

Heisenbug

This ones based on Heisenbergs uncertaintity principle. In which the act of observing affects the measurement of the thing being observed. In software this is a bug that appears but that act of trying to debug it makes it go away. Bugs that only appear in release versions of code are classic examples.

Signtool and Get-AuthenticodeSignature

October 9, 2007

In my previous post on checking how much signed code is on your machine I used signtool.exe to verify if a file was signed. Powershell has a built in cmdlet called Get-AuthenticodeSignature for doing just this. So why did I use signtool?

Lets try a little test on good old notepad.exe

With Signtool.exe we get:

signtool verify /pa /a c:\windows\notepad.exe

Successfully verified: c:\windows\notepad.exe

and with Get-AuthenticodeSignature we get:

(Get-AuthenticodeSignature c:\windows\notepad.exe).Status

NotSigned

So signtool thinks its signed and Get-AuthenticodeSignature doesn’t. Notepad is signed but in a slightly different way to other files. OS files in Windows use catalog files to store their digital signatures. Signtool can be made to check these catalog files, which gives us a more accurate result when we are checking the amount of signed code on a system.

Is it signed?

October 4, 2007

Code signing is a great technology. Every software developer should be signing the code they produce. But how much of the code on your system is actually signed? Time for a little Powershell script to find out.

The easiest way to check a digital signature is with signtool.exe

$env:PATH = $env:PATH + ";C:\Program Files\Microsoft Visual Studio 8\Common7\Tools\Bin"

$startloc = "c:\windows"

set-location $startloc

$res = 0 $tot = 0

get-childitem -recurse | where {$_.Extension -match "exe"} | foreach-object {

signtool verify /pa /a /q $_.FullName

if($LastExitCode -eq 0) {

$res = $res + 1

write-host -foregroundcolor:green $_.FullName

}

else

{

write-host -foregroundcolor:red $_.FullName

}

$tot = $tot + 1

}

$pc = ($res / $tot) * 100.0

write-Host "Results" write-Host "Signed: " $res write-Host "Total: " $tot write-Host "Percentage Signed: " $pc

Running over the windows directory gives 90%, showing that virtually all the Windows system files are signed. Running over C:\Program Files gives a less impressive 13% on my machine.